The Perfect Book Title | Lex Academic Blog

Titles can raise questions, suggest imagery and conjure up entire worlds. They may, of course, also inform prospective readers of a book’s contents. But authors do not always intend to use them in this way, or necessarily succeed when they try. As the comedian Dan Wilbur points out, books don’t necessarily give an impression of a book’s contents, so he started a website – betterbooktitles.com. ‘I will cut through all the cryptic crap’, he promises, ‘and give you the meat of the story in one condensed image’. In his hands, Plato’s Symposium becomes Horny, Drunk Guys Invent Philosophy and Moby Dick becomes Every Alliterative Life Lesson Learned by Boastful Boatmen at Sea. He’s obviously playing it for laughs, but he has an important lesson to impart: a title needs to convey the main themes of the work, be concise, and attract readers.

In the late 1860s, the philologist Frederick Furnivall was confronted with the unsuitability of pre-modern titling practices when he founded the Chaucer Society. His aim was to honour the great poet’s memory by reprinting and republishing his works, but there was a problem: Chaucer worked at a time before extensive libraries, bookshops and catalogues. He wouldn’t have expected his work to be printed, reprinted, bought, sold and archived.[1] And this meant that many of his works had multiple titles. The Legend of Good Women, for example, was variously titled ‘my Legende’, ‘a glorious legende / Of goode wymmen, maydenes and wyves’, ‘the book of the XXV. Ladies’, and ‘the Legende of Cupide’. Other works had no titles at all. It therefore fell to Furnivall to settle on the titles. One poem had no fewer than twenty-three titles, as well as several untitled versions, and Furnivall rejected them all in favour of his own: Truth.

Pre-modern titling conventions allowed works to acquire and lose titles at any point in their production, or even their circulation and criticism. The author or scribe could give a title, writes book historian Victoria Gibbons, but so could a rubricator, illuminator, compiler, stationer, binder, patron, owner or reader. By the nineteenth century, all this had changed. Books, poems, articles and other works were expected to have titles. Since at least the Statute of Anne – otherwise known as the Copyright Act – in 1710, titles have also been important legal instruments, meant to designate the ownership of intellectual property.[2] Titles are derived from a work, a distillation of its contents, and as Isaac D’Israeli – the writer and father of British Prime Minister Benjamin D’Israeli – put it, they also provide ‘some amusement’.[3] By finding a modern home for Chaucer’s work, Furnivall and the Chaucer Society had to assign titles enabling it to exist in a modern context, bringing it from a primarily oral tradition to a paper-based eco-system of printers, library catalogues and bookshops.

Some titles have an aesthetic and artistic integrity that endure even in the absence of an accompanying work. In 1851, Charles Dickens ordered a fake bookshelf filled with whimsically titled fake books to disguise the entrance to his study at Tavistock House. Socrates on Wedlock joined Was Shakespeare’s Father Merry? and its companion Was Shakespeare’s Mother Fair? His collection was complete with all nine volumes of Cats’ Lives. Dickens enjoyed the whimsy of creating titles without books so much that he ordered another fake bookshelf when he moved to Gad’s Hill in Kent. You’d find a similar bookshelf at Chatsworth House, where one book promised to give readers an insight into how lambs feel about suet. And a visitor to the library at Aldermaston Park might consult the Logbook of the Ark. Victorians weren’t the only ones who loved a title without a book. The Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges created fictional books to feature in his short stories. Many years later, in 2020, the artist Emma Falconer found his titles so evocative that she designed covers for some of them.

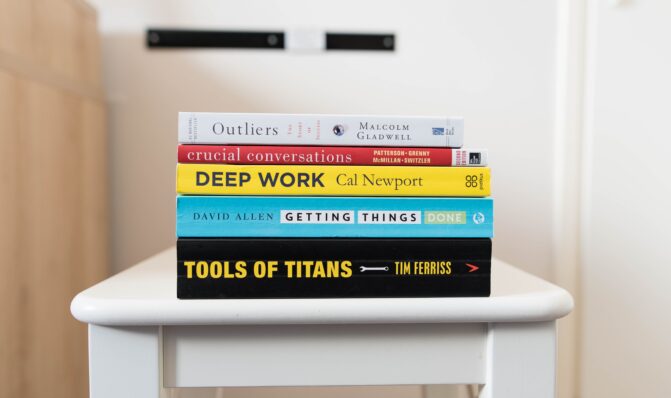

For non-fiction in particular, including academic titles, the needs of a library and bookshop give us a seemingly obvious place to start when creating our own titles. Anyone penning a title today will obviously require it to be clear, descriptive, attractive, consistent with the content and regular across all future versions.

All of this is applicable to modern academic texts, where titles also act as the distillation of a work, a series of descriptors and aids to archiving and finding. Academic titles can (or should) still adhere to the list above, although academic books and articles are also technical documents, so scholars have additional needs: they must take account of search engines and other ways to label or tag works, such as keywords. Such special consideration allows fellow researchers and librarians to find works and associate them with one another. The writer Kevin Jackson wrote that good titles have a ‘magic’ about them.[4] Arguably the hardest part of coming up with a title is making it memorable and magical. Your peers might be a good sounding board, and title generators are an (imperfect) way to find inspiration. Unless you’re writing a trade book, though, nowadays ‘magic’ is far from any academic’s mind. Non-fiction authors are sometimes advised to write down the problem that their work addresses or solves. For academic texts, we might more usefully suggest a different kind of clarity: constructing a title from keywords, themes, your field and even methods. Just as Furnivall had to re-visit Chaucer’s titles to accommodate his works into a system of libraries, bookshops and catalogues, scholars nowadays find books electronically and our own titling practices must take account of this relatively new reality.

J.G. Frazer’s classic anthropology text The Golden Bough, for instance, might have a pithy, richly expressive title, with its laconic reference to the endless cycle of death and rebirth, but if Frazer created that work today, an editor would probably ask him to reconsider. He’d have to sketch out something optimised for search engines (and judging by the number of times he references ‘savages’, he’d probably also be assigned a sensitivity reader). A more up-to-date title would be relatively exhaustive, trying to make the work as transparent and searchable as possible. Perhaps it would include a reference to his methods, the dates his study fell into, even a clue to his results.

Here’s an example of a modern title, designed to be found by modern means: ‘A Comparison of the Progressive Era and the Depression Years: Societal Influences on Predictions of the Future of the Library, 1895—1940’. For this title, the author has included keywords and dates, and ensures that the reader can already place the article in relation to a discipline, field, and even their peers’ work. Another example, this time for a book: ‘Making Sense of Medicine: Material Culture and the Reproduction of Medical Knowledge’. Again, the themes (sensation, reproduction of medical knowledge) and field (material culture) form the title, so scholars working on material culture, sensation or theories of knowledge – or any combination of those three things – can easily locate and judge the relevance of the text. Subtitles can be added to aid clarity, such as the book by Maximilian de Gaynesford about the first-person singular, originally called ‘I’. A title couldn’t get much pithier, but you wouldn’t have much luck typing ‘I’ into a search engine. The subtitle, ‘The Meaning of the First Person Term’ made it searchable.

The turn towards clear titles is a bit like Dan Wilbur’s alternative titles – academic works must now be transparent, so neologisms and sexy wordplay will be harder to find. It’s hard to love such titles, but they aren’t designed to be loved. They logic we follow in creating them is arguably an extension of that governing earlier titling practices for print culture: titles aid archiving, storage and retrieval, not to mention the need to associate a work with an author for copyright purposes. Unless you’re David Sedaris, who called his first volume of diaries Theft by Finding because he heard a friend use the phrase and liked the sound of it, there needs to be some logic behind a title (and Sedaris admits, in Theft by Finding, that his editor complains about his ‘wilfully obtuse’ titles – he only gets away with it because he’s famous and fans search for his name, rather than a particular text). Most academics aren’t searched by name, so our titles have to be carefully chosen in accordance with the way archives, libraries, and booksellers organise and store books and articles, and the way scholars search for them. As we change the way we identify and read texts, our titling practices must follow suit, just as they always have.

[1] Victoria Louise Gibbons, ‘The manuscript titles of Truth: Titology and the medieval gap’, The Journal of the Early Book Society for the Study of Manuscripts and Printing History 11 (2008): n.p.

[2] Eleanor F. Shevlin, ‘“To Reconcile Book and Title, and Make ’em Kin to One Another”: The Evolution of the Title’s Contractual Functions’, Book History 2 (1999): 42–77, 43.

[3] Isaac D’Israeli, ‘Titles of Books’, in Curiosities of Literature, ed. Benjamin D’Israeli (London: Warne, 1881), I. pp. 288–93, 288.

[4] Kevin Jackson, ‘Titles’, in Invisible Forms: A Guide to Literary Curiosities (London: Picador, 1999), pp. 1–17, 11.

Be notified each time we post a new blog article