‘Coming Out’ as Working Class in Academia | Lex Academic Blog

A disability studies scholar once managed to raise an eyebrow of mine by dropping into conversation the term ‘super cripple’. Quite an offensive expression, I thought. But he assured me he was serious and this was a scholarly concept. ‘Super cripple’, he told me, referred to the rare individual who, despite their disability, not only manages to integrate into society but to excel in some way. They’re the heart transplant patients that run marathons, the paraplegics who found companies, the successful dancers who continue dancing despite partial paralysis. Rare and remarkable lives make compelling stories, but the ‘super cripple’ phenomenon has a dark side. If the hearing-impaired Dame Evelyn Glennie can make it in music or Stephen Hawking can become a famous theoretical physicist and cultural icon, then you, too, should be capable of achieving greatness. So, if you don’t manage to integrate well into society, you must be at best lazy, at worst a scrounger.

A few years later, when I ‘came out’ as working class, I was reminded of the ‘super cripple’ concept. On one occasion, a middle-class colleague – a professor in a highly selective Russell Group university – was complaining to me about her own unhappy position. Her pension was ‘tiny’, she said; the benefits ‘awful’. Her institution was ‘going down the drain’, with standards of research ‘slipping’, and the leadership ‘all over the place’. I’d been working with this professor intensively for the last three days, and I’d heard her complaints and all their variations as an almost constant drone accompanying our work. To my shame, something in me snapped. ‘But you own an entire house in Zone 2 in London,’ I blurted, ‘and you have a permanent position, pension, and a husband with a good job. And what’s more, you know my circumstances. You know I’m employed on lots of little casual contracts with different institutions, in a rental trap without the hope of buying even the tiniest of flats’.

Silence. I knew I shouldn’t have said that. My colleague’s cushy position was under threat, too, and though my case was far worse, she wasn’t to blame and we shouldn’t be fighting. I was ready to apologise for my outburst when the tension escalated. ‘Then why did you prioritise writing a trade book instead of an academic book?’ she asked. ‘The trouble with you is that you know you should be doing one thing, but then you go and do another’.

‘Because it paid’, I said, thinking it obvious that rent and bills wouldn’t pay themselves, and that we needed to eat.

‘You were being mercenary’, my colleague, a self-professed socialist, countered. ‘If you really want an academic career, you can still cancel your book contract, work on fewer projects and write your academic book instead’. Then she named an elderly social scientist at another institution who also came from a working-class background but had nevertheless ‘made it’.

It was this question that made me relate to the ‘super cripple’ phenomenon. The existence of working-class people with jobs in academia seems to be taken as proof that we have no insurmountable obstacles, and every reason to succeed. Like the beneficiaries of the toxic housing market boom who insist people under 40 can buy a house if they’d only stop drinking flat-whites, I was effectively being told that the only thing holding me back from a professorship was the fact that I didn’t want it enough to make the sacrifice.

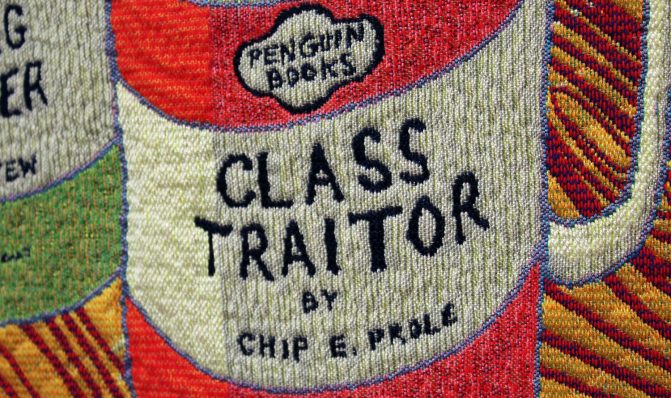

It’s been about three years since this bad-tempered exchange. My book has now been published – to critical acclaim, I am grateful to add. It even won an award from the Royal Society of Literature. In academia, though, that same publication has become evidence in a case against me. As my colleague intimated, it seems to be taken as a lack of commitment to academia. Without a corresponding academic tome – something I’d have to write and publish without payment – it’s a nice, if practically worthless, example of an engagement activity. This is one way a working-class background has been an obstacle to getting on in academia: how can one produce the necessary goods without material support? I’m now an Early Career Researcher, but I have never succeeded by going through the front door. I’ve learned that the system doesn’t want my type, and at every point in my career I’ve found an unofficial, sneaky, back-door way to get academic work.

I’d supported myself in the most precarious first years of my career, for instance, by becoming a film-maker. I made my first films during my PhD to supplement a scholarship paying my fees, plus a £3,000 stipend. Films are fairly expensive to make, so I could earn enough money that way and still have time to write my thesis and, later, the peer-reviewed articles I needed in order to apply for a postdoc. This enabled me to survive, but it took time to make films, let alone run a limited company and hire the staff I needed. The problem was kicked further down the line – by the time my first few articles were published, I was more than three years post-PhD. And this meant I was no longer eligible for most postdoctoral fellowships, which tend to hire only fresh PhDs ‘in fairness to other candidates’. I had to find another way forward.

It was a little hard to watch independently wealthy and parentally assisted peers snap up the postdocs while I worked full-time to fund the writing time they took for granted. I’ve been able to continue making academic work for one reason: open-minded, interested, wonderful colleagues have taken a personal interest in my work. And they helped me open further back doors. I’ve worked on academic projects where I started as a film-maker and been introduced to more interesting, scholarly conversations that way. I’ve worked on other projects where I’ve been included in someone else’s grant, which allowed me to sidestep the usual requirements and be parachuted directly into temporary research posts.

Since my ‘coming out’, I’ve been told by middle-class academics that I don’t belong in academia and that I should be grateful to have any kind of platform. Fellow working-class academics have told me that I shouldn’t be working with ‘elitist’ Russell Group universities. And people I’ve known for most of my life have accused me of being a traitor to my class for having anything at all to do with higher education. But it’s been the financial, material obstacles that have constituted the greatest difficulty. I started a limited company so I could supplement an inadequate scholarship; I wrote a trade book instead of an academic one so I could still write while living off the advance; and I carefully fostered networks with colleagues who brought me into their research groups in unconventional ways.

There are working-class academics, of course, but we are the exception. Yet, as with the ‘super cripple’, our very existence – even as a tiny minority – sends the problematic message that careers are there if you want them badly enough. When my colleague dressed me down for choosing trade over academic publishing, she refused to acknowledge that I couldn’t simply do what needed to be done. Blind to an ordinary person’s need to make ends meet, she could only invoke a rare example of a successful working-class academic and ask: if they can do it, then why can’t you? But this missed the point. One must have the right cultural background, social connections, and economic stability to even consider entering academia by the front door. Even then, the employment market is such that all but the most privileged of us struggle to get a job. If you have caring responsibilities, have had a less-than-straightforward career path, or simply haven’t got the family income to support you through the years of early-career precarity, your route into academia – if you can find one at all – is bound to be unusual. It feels like the academic journey is rigged against us, and if we are going to make things fairer, we need to recognise that working-class scholars are the exception, and their experiences and career pathways can’t be taken as representative.

Dr Paul Craddock is Honorary Senior Research Associate in the Division of Surgery and Interventional Sciences at UCL Medical School in London. His PhD explored how transplants have for centuries invited reflection on human identity, a subject on which he has also lectured internationally. Published by Penguin, Spare Parts: A Surprising History of Transplants, which won a Special Commendation from the Royal Society of Literature, is Paul’s first book.

Be notified each time we post a new blog article